Making the Case for Complementary Leadership

Ensuring that 5 + 5 + 5 = 18.

Enjoying Making the Case? Give a gift subscription to someone else who might enjoy it.

The Brief Case 📚→💼→📈→📊

It’s not being conventional that helps a team win. It’s maximizing what you’ve got.”

Ed Smith in Making Decisions: Putting the human back in the machine

Considering the potential of your school’s board is an interesting exercise. You might start by assigning a score to each member, with 5 being the highest. But then, what would you be evaluating? John might have significant financial expertise, which is great for a school likely run by educators turned administrators. Nancy might be a tech executive with a deep engineering background — ideal for a school with a 1:1 laptop program or aspirational STEM goals. Diane might be a newly retired Head who brings fundraising prowess to a school beginning a new capital campaign. All good.

But are John, Nancy, and Diane all 5s? Sort of. Or rather, it may or may not matter. As subject matter experts (SMEs), they are all well equipped to be major contributors to a school’s board. That doesn’t mean that their presence at your next board meeting automatically gives your board a starting score of 15 in terms of its potential. 5 + 5 + 5 could very well equal 15; just as likely, it could equal 9 . . . or 18.

SMEs (like superheroes) are often accustomed to working alone or in a context that amplifies their individual contributions. High functioning boards or administrative councils (super teams) work together and often in contexts that challenge their ability to first cohere and then contribute. The sum of the parts of a team will only add up to 15 (or even 18!) if someone clears the way for work that isn’t isolated (by individual) and then expected to add up (by team). Instead, such effort needs to be elegantly and intentionally conjoined — made complementary — from the start. Such leadership produces outcomes that could only be created by a particular group of people, working together, at a particular time, and in a particular space.

📚 The Learning Case for Complementary Leadership

Let’s dwell for a moment on how 5 + 5 + 5 might equal 18, and why this is a useful equation to carry around in your head when thinking about school boards or leadership teams.

If a team of high functioning individuals is itself functioning at an extraordinary level, the potential of the team’s members should be arrived at not by looking at them in isolation and as they appear when they walk into a room or meeting. Instead, it should be arrived at by dividing the total output of the team by the number of team members.

So, in the right environment, with the right leadership and agenda, team members who walked in as a 5 (considered the top in our model) could end up contributing at the level of a 6. We — or rather, our model — would be selling them short if we only viewed them as excellent in a singular way (finance, tech, fundraising) or if we never even realized that we could make them better than a 5 by connecting them to others in the right way, via leadership (and a different model!).

To see how this stretching of talent by cultivation of team (SOT by COT) might happen, let’s return to John, Nancy, and Diane, our SMEs. When they walk into a board meeting, they likely either expect to get up to speed or hope to contribute in a way that only they can contribute.

But what if Diane (former Head) is assigned to lead a subcommittee on STEM initiatives, and her two team members are John and Nancy? How should she approach this task so as to maximize the output of the team and amplify the talents of the team members? We’d recommend that she first think about what might be called her “leadership settings.” By turning down her “deep” fundraising skill and turning up her “soft” facilitator skill (the one that made her a good all-around Head of School and not just a good fundraising Head of School), she would enter the subcommittee’s meetings in an entirely different way.

With fundraising turned up too high, she would likely only listen for moments where she could attach that expertise — whether gracefully/organically or less elegantly — to the tasks or discussions at hand. With fundraising turned down and facilitation turned up, though, she would instead focus on ways to make John’s financial skills mesh with Nancy’s tech vision in order to promote possibility — in an area of priority — for the school. Using her facilitation skills to balance John’s and Nancy’s skills and perspectives, in fact, would be essential in making sure that the subcommittee didn’t lean too far to one side, making them skip over options because they are not pragmatic enough (John’s likely bias) or making them suggest options that have no chance of being implemented in a school with necessary constraints (Nancy’s likely bias). The possibilities suggested by a properly calibrated group (a super team) of 3 SME’s (superheroes) might add up to 18 rather than 15.

So, before you can even begin to understand the potential of your board or your leadership team, you have to shift from accessing (and then adding up) individual contributions to accessing a team’s unique contribution. Leaders looking to unlock the latter promote and shape their teams’ ability to share what they knows in order to build something greater than the sum of what they know. They see a group as a giant brain rather than a bunch of isolated brains.

💼 The Business Case for Complementary Leadership

Now let’s dwell on the opposite scenario: how 5 + 5 + 5 can equal 9 (rather than 18). This, too, is a useful equation to carry around so that you can quickly scan the teams you are on (or lead) and the rooms you are in.

You may end up with 9 if you do not weave enough “complementarity” into your team. In “The Leadership Team: Complementary Strengths or Conflicting Agendas?”, Stephen A. Miles and Michael D. Watkins outline four different ways to combine the skills, talents, and perspectives of a talented group of people.

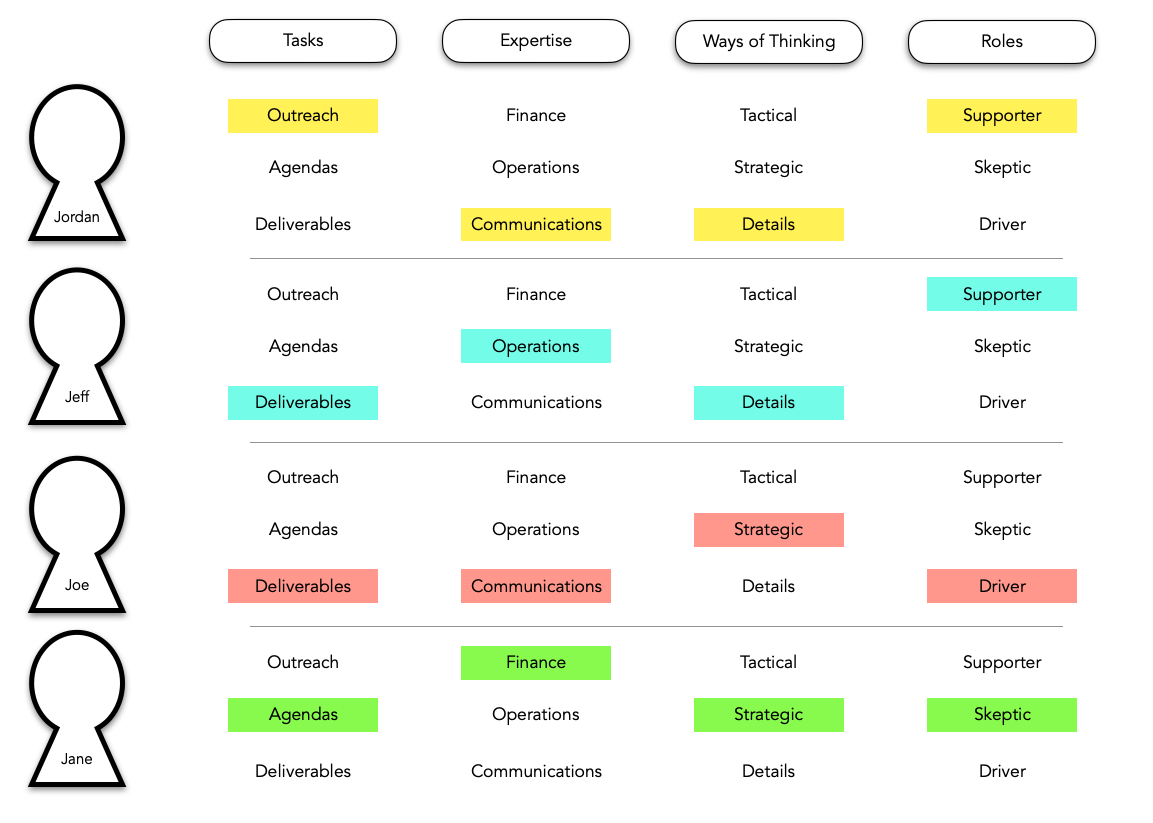

Task complementarity occurs when leaders “divide management responsibilities into coherent blocks of tasks.”

Expertise complementarity occurs when a leader chooses to focus on the particular skills, training, and wisdom of each team member. Regardless of the general, everyday skills they bring, team members, in this case, will be asked to contribute using their key strength.

Cognitive complementarity occurs when a leader takes into account “how individuals process information.” (Think details or big picture, vision or implementation, strategy or tactics, words or numbers, etc.)

Role complementarity occurs when leaders acknowledge and allow for the fact that there are many social roles to play in an organization and “one person can rarely assume more than one.”

Boards or leadership teams offer the perfect opportunity to promote some or all of the above kinds of complementarity — which of course only works if you have enough variety on the team and/or you actually seek to amplify the variety on the team. To return to our original SME scale, there are two ways for individual value to be reduced on a team. First, having too many of the same kinds of 5s in the room leads to diminishing returns (it’s okay to have overlap). Second, treating different kinds of 5s as if they are the same kind of 5 leads to diminishing returns.

Put another way: When team members are being evaluated for a team’s output, it doesn’t matter that each one is brilliant in their field; to apply an old adage, if all your team members are hammers, then every problem looks like a nail. All problems also become nails if you treat your team members as if they are all hammers. And problems these days are likely — usually — much more complex than nails that need hammers.

Example # 1: No leadership move in the world can help a group of brilliant thinkers with poor or even average communication skills make a great pitch to constituents and then communicate milestones in an ongoing and effective way. In this example, the brilliant solution will forever lag behind its potential, and then the chatter will begin: was it really that brilliant after all? Complementarity (blending expert vision with expert communication) could help.

Example # 2: The best communicators in the world selling a mediocre (or worse) idea will not inspire people to want to make the kinds of extraordinary efforts that lead schools to ongoing excellence and growth. Such team outputs will lead the team to be viewed as all flash, at best, and deceptive, at worst. Complementarity (blending expert communication with design thinking or product expertise) could help.

A leader adept at deriving a particular benefit from a particular team by using the particular skills on the team is able to activate individual’s subject matter expertise when needed and is able to bring things (and people) together when needed. Such agility is often flexed through the most overlooked tool in a leader’s toolkit: the humble meeting. Instead of both leveraging the strengths/gifts of those in the meeting and mixing the strengths/gifts of those in the meeting, meeting leads often reduce all to equal participants. When full boards and full admin groups are together, therefore, those meetings are often designed for reporting rather than doing, and in the process, for making the room add up to 9 instead of 18.

At the very least, consider balancing the mix of vertical and horizontal tasks on your agendas. Vertical tasks can be completed in isolation; they can require individuals to do what they do best or report out on an area, and using a vernacular, that expresses their strengths and deep expertise. Horizontal tasks encourage those same SMEs to turn to other, quite different SMEs, to create a hybrid solution, one that can only emerge from a meeting where people are asked to make meaning, to develop prototypes or solutions, to actualize, to invent, to do.

More dramatically, consider scheduling more retreat style work with your key leadership groups (not just 1x or 2x a year, but maybe 3x or 4x) and then eliminating some of the reporting or even voting meetings. Such tasks can be mediated electronically. Imagine what might happen if you only called your most talented people together when the work would be maximally meaningful and impactful.

A word about growth: we’re not suggesting that people should not grow as a result of their time on a board or leadership team. In fact, growth is one incentive for people to actually join boards or to accept leadership roles. But by the time someone is seated on a board or senior leadership team, they should have some experience and/or skills that have compounded enough to put them fairly far ahead — due to a fairly defined strength — of others who might just be dabbling in a given area or newer to it. It’s good to grow; it’s also good to be called on to do the thing you’re best at; better still is to serve alongside a leader who has mastered the art of SOT by COT.

📈 Return on Investment for Complementary Leadership

The return on investment in complementarity comes from “speed to shared understanding.” Leading a group to common understanding and alignment around issues helps decisions to happen in better, more timely ways. On the flip side, if you do not spend your team’s time well, you are wasting money, good will, and intellect.

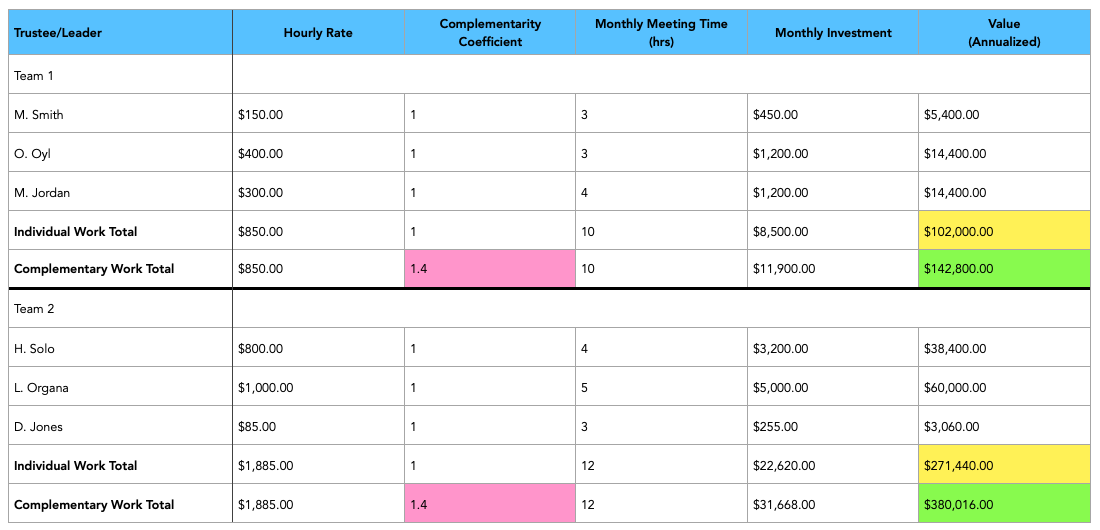

Measure the value of complementarity by first measuring the value of your team members (time x rate). For employees of schools, most HR platforms have an hourly rate for every employee, including annual salaried employees, which can be used to calculate this estimate. For Trustees, you can put an hourly rate on their time volunteering and/or offering their professional expertise and how it is valued.

Next, design a “Complementarity Coefficient,” representing how the combined value of two or more of the right people working together in the right ways is worth a multiple of their individual rates. That is, the value the school might derive from any member’s individual contribution is less than the value of that individual complementing the right other individual(s).

The results will help you to better understand, if not measure and show, the engagement and efficacy of such work. Every hour that is mis-used is a cost to the school (good-will or actual capital). When, on the other hand, the right combination of time and talents are used, you end up creating a value that only exists because of that combination.

📊 Return on Learning for Complementary Leadership

The next time a team meets — or you are forming a team — use a chart to identify the tasks to be done, required expertise and thinking styles, and roles to be played. Then, identify (a) which team members are best able to serve those functions and (b) where you are missing representation.

Making people aware of their own skills/dispositions/talents and the skills/dispositions/talents of others will serve two purposes.

First, it will elevate the general understanding of the composition of the team. Once that understanding is cemented, it can aid problem solving because the team knows where and when to pass the ball (to Jordan, to Jeff, to Joe, to Jane). Additionally, the team knows when to look outside of itself to pull in needed expertise.

Second, people on self aware teams also have increased opportunities to learn from one another. The great technical expert should become a better communicator while working with a marketing expert charged with presenting that expert’s design. The brilliant writer should become more culturally competent as his text or speech is reviewed by a highly skilled Diversity and Inclusivity practitioner.

Ideally, your team will include a few people with similar strengths/talents in addition to a broader range of complementary skills. In fact, it’s ideal to have overlapping skills rather than one mindset/skillset in isolation. You want people to speak enough of each other’s languages to be able to build shared understanding, while also being able to go deep in a given field or speciality when the team requires such work.

More on this Topic

Opinions

💡 The Leadership Team: Complementary Strengths or Conflicting Agendas?

💡 Reinventing Your Leadership Team

Examples

🎯 Successful teamwork: A case study

🎯 Developing and Sustaining High-Performance Work Teams

Research