The Brief Case 📚→💼→📈→📊

The term “eating one’s own dog food” doesn’t conjure the most pleasant of all thoughts; nonetheless, it conveys an important truth for school boards and leaders.

When it comes to learning and social dynamics, mission-driven schools cannot afford to offer one dish — one take on learning, one take on social dynamics, one set of expectations — while living off something else entirely. It would be a bit easier to see (and swallow) if we were arguing that insurance salesmen should insure their families with the product they are selling, or automobile salesmen should drive the same car that they present most passionately to their customers. Eating one’s own dog food, like eating the frog or having skin in the game, is an essential business aphorism.

Here’s a more palatable, school-oriented way to think about it:

Teachers work every day to increase the understanding of their students. Walk the halls of any functioning school and you’ll see them, class by class, doing anything they have to do (we can call this, loosely, pedagogy) to help students understand where commas go, how formulas work, or why our government was designed the way it was.

Schools that, themselves, aspire to learn have a commitment to understanding, as well. Walk into the meetings of a school that learns and you’re likely to see leaders building understanding among teams or divisions or constituents. You might hear about why a new project, and the disruption it will cause, is critical to the school’s

future, or why a school’s budget is shifting, or how faculty support of the school’s annual fund will be essential for cultivating larger philanthropic gifts, or how SEL work supports academic work.

At base, such understanding building is mere internal communication (i.e., “We’re planning X, so we need to be sure to tell this group and this group”). Another rung up the ladder of understanding building is paying attention to audience when composing school policies or guiding documents and shifting such documents as needed to serve different audiences. The next rung up is the act of translating, when necessary, the language of one discourse group (say, the business office) into language that another discourse group (say, the faculty) can grasp. The top rung, i.e., the most aspirational rung, is helping all lead communicators in a school to become better teachers — that is, to move them into the mode of building understanding, taking responsibility for understanding, so as to inspire action.

Investing in understanding, and what it takes to build it consistently throughout a busy school year, is a worthwhile discipline. Why? Because understanding of the right kind leads to action of the right kind. Also, understanding of the wrong kind leads to action of the wrong kind, and understanding that is all over the map leads to uncoordinated, hectic, and inefficient behavior. The choice here is clear.

We’re making a case for reducing the dissonance (i.e., misunderstanding) within an organization that leads to unhelpful friction. As a clarification, we’re not opposed to the kind of friction that makes good ideas better, but we’ll save that case for another time.

📚 The Learning Case for Eating One's Own Dog Food

When a school’s beliefs and practices about teaching and learning are reflected in the school’s organizational practices, that school has the necessary ingredients to be a learning organization. Put simply, schools that function as learning organizations work perpetually to reduce disconnects between what they say they value and what is actually lived and experienced within a school’s ecosystem.

A true learning organization can be seen as a set of equitable and clear parallel expectations. That is, in school, our expectations for social and interpersonal interactions among kindergartners should resemble what we expect of seniors, parents, and colleagues. The scale changes; the DNA does not.

We ask students to be brave, to take risks, to be kind, to be clear — and should hold the organization to the same standards. How we design for learning should inform how we design meetings, presentations, and community time. How we assess learning and learners should be how we assess work and workers. What we expect around DEI for a sophomore should be what we expect in that area from a sophomore parent. Discontinuity chips away at the specific type of learning experience that the school is designed, in the first place, to deliver.

Here’s what learning-centered communication might look like outside the traditional classroom. It comes from an interview with Tami Simon, global corporate business leader at the benefits and human-resources consulting firm The Segal Group. Simon's research and experience suggests that leaders in the HR and Business functions of a school can enhance faculty well-being by communicating beyond a mere memo or announcement.

When asked about best practices regarding communication, Simon says:

More is more. Repetition helps. Using a variety of different communication strategies, just like with any good marketing campaign, is really important: website, text, meetings in person, virtual meetings, little webinars, maybe a blog. Not everybody learns and understands things at the same level or in the same way, so we use all those different communication techniques when we're talking to a variety of different audiences and levels of sophistication. And I am a huge advocate of examples, examples, examples.

She calls this marketing, but we overhear good teaching in what she describes. She encourages HR and Business professionals to vary their delivery, to use multi-modal approaches, and most important, to consider the learning styles of an audience — the faculty, in our case — often seen as monolithic.

As a leader, one of your ongoing challenges is to keep the standard of communication high — and such work will lead to a natural payoff. If adults continuously work to address other adults in a manner that stimulates learning, many other interpersonal dimensions will be served. That is, in each adult exchange, they will be kind, patient, and encouraging; they will build in formative assessment and use it to adjust their approach; they will seek to know, in a deep way, the person (learner) in front of them; they will feel a sense of accountability to the person’s learning and to what they are ultimately able to do as a result of the instruction.

Now imagine if the students in your building overheard such work unfolding or simply benefited from it trickling down to them. When everyone is committed to the learning beliefs of the organization and experiences those beliefs in practice, a virtuous cycle is likely to ensue.

💼 The Business Case for Eating One's Own Dog Food

Understanding is important because it informs action, or at least it should. A corollary to that idea is that it is important to shape understanding to lead to the action you hope to see on a team, in an organization, or in the world. Churchill said, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.” The same logic applies to our topic at hand: We shape understanding; thereafter understanding shapes us.

In an interview with Anti-Racism Daily (ARD), Dr. David Parker, Vice President of Research and Development for ServeMinnesota, mentioned that reading the publication is like a daily meditation for him. What’s more, he asks his team to include ARD in their individual workflows. Reading in such an intentional way is a lever for learning. It’s a clearing of space for consideration and re-consideration, for putting ideas next to ideas, for getting clear about what you understand, what you don’t understand, where you need to turn next. And, once that is settled, just-in-time adjustments to practice can flow freely. According to Parker, the understanding his team builds by engaging with ARD has specific consequences:

That’s been a huge contribution to our organization’s baseline equity and anti-racism skills. It’s impacted our funding priorities as we moved away from relationships with certain funders. Some of us can articulate the racist mechanisms between a guy like me talking more in a meeting and can identify some of our colleagues who are not yet aware of that and are working on it. We’ve had hiring and promotions that have been more equitable, representative, and hopefully inclusive.

Shaping and updating understanding is not mere abstraction. Indeed, changing your understanding is changing your software is changing what comes out of the software. Mission-informed input leads to output that becomes proof of that mission.

Here’s a useful image to keep in mind:

Think of your institution as a rocket ship filled with constituents. If your mission were completely generic — e.g., we’re a school that keeps students safe and educates them — then the rocket ship, when launched, would move straight up in the air.

A mission-inflected learning organization, however, would veer a degree or two to one side. Sure, it needs to be generic in certain ways — e.g., safety — but it veers, necessarily, because it has a unique approach that its constituents understand, appreciate, and enroll into. This understanding, appreciation, and enrollment leads to engagement, participation, and constituent actions. It also leads the rocket to land in a completely different place, in the long run, than the generic rocket will.

If you’re communicating well — teaching to build understanding — your rocket will land on Mars and your passengers will be on Mars. If not, don’t be surprised if your rocket lands on Mars and your people end up on Pluto. That’s a long term business risk that you cannot afford to take.

📈 Return on Investment for Eating One's Own Dog Food

We mentioned earlier that when school employees are committed to making sure learning beliefs are put into practice, such beliefs and practices become self perpetuating — a virtuous learning cycle.

Admittedly, the start-up (or restart) cost of such a cycle is an ongoing challenge. Big interruptions — from pandemics to social reckonings to political climate shifts — can cause the need to emphasize / deemphasize different aspects of our programs or to break or make certain institutional habits. More common, as in every year, too, we face the smaller scale costs of onboarding new teachers, updating our practices to abide by new laws, or re-skilling as we seek to evolve in necessary ways.

As we invest accordingly in professional development and the resources that support ongoing learning (professional coaches, instructional coaches, time in the calendar), the return can be measured across many indicators.

We suggest using employee retention and speed to filling open positions as key markers of successful learning organizations. The best way to quantify this is using the cost of recruiting, hiring, and onboarding new employees.

Three relevant metrics can be easily measured. First are the costs for recruiting with external parties (i.e., job posting and agency fees). Second is an internal measure based on hiring managers and hiring teams and the above normal time they are spending as they lead or participate in searches. A final measure is around any programming and procedures (internal or external) that bear a cost to the school (again, including the above normal time of various offices and people spent supporting new colleagues).

A good learning organization would see the cost of hiring reducing year-over-year if a larger portion of the workforce is retained. Schools will never avoid having some annual turnover, but keeping the people who are leaving because they are not happy or finding what they need can be addressed through these efforts.

Employees that feel consonance in an organization should be more likely to stay and contribute to the learning cycle. When there are open positions, too, top talent will be begging to join the institution because of its reputation as a learning organization.

📊 Return on Learning for Eating One's Own Dog Food

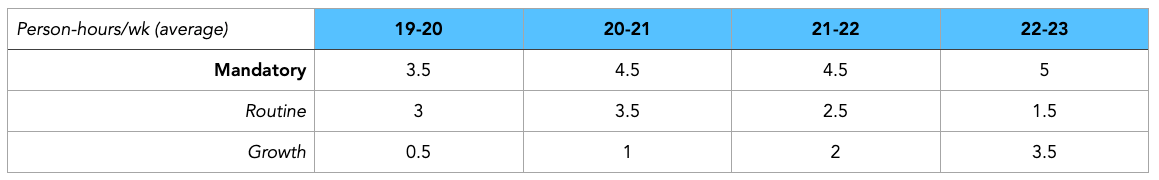

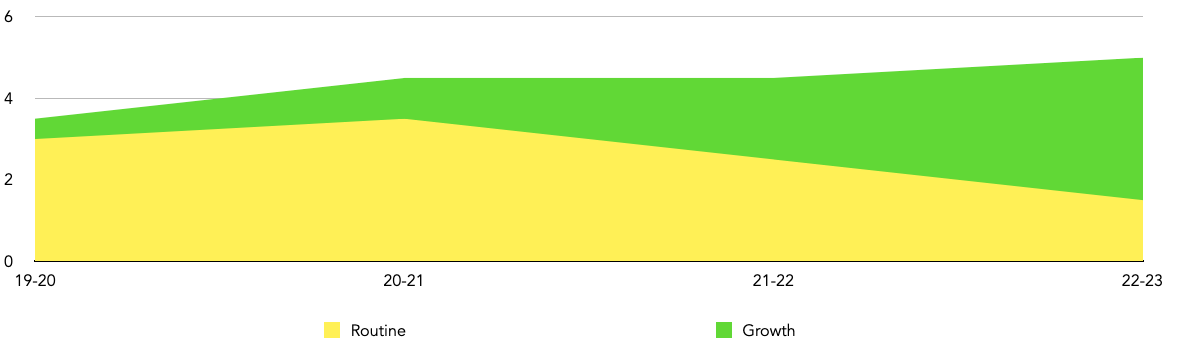

Measure the return on learning — for behaving as a learning organization — in two ways. First, make an annual index of cross-department group meeting time (cross department teams, divisional meetings, all-hands meetings) and set baseline targets for time spent on growth activities (doing things in a better way for the long term including strategic work and professional growth) and time spent on routine activities (day-to-day, month-to-month, and year-to-year work).

You may not be able to change the time needed to address the routine (though we’d argue that there are always pathways to reclaiming strategic time from the routine), but you can shift the balance between growth and routine by having more time allotted for organizational learning.

Second, make a yearly measure of the voluntary professional development time committed by the work force.

Voluntary PD describes the activities (conferences, courses, school visits, etc.) that signal that folks are intrinsically motivated to learn AND that the organization has committed the resources to support their learning (travel funds, responsibility coverage, etc.).

Software industry experts have described the benefits of a “dogfooding mindset” as including product validation, limit-testing, and internal/external messaging. In schools, good learning science and instructional design do not need to be validated or proven. Neither students nor teachers should be permanent experimental subjects. And marketing spin should never be a primary or secondary goal of any effort; if a school is doing a good job, the story will not need extra spin.

The benefits of dog-fooding for schools, instead, can be seen in enhanced morale, aligned sense of purpose, and increased ease by which learning happens (for students and employees) across the institution. Such schools deserve the attention and care we put into them.

More on this Topic

Opinions

💡 School Mission Statements: Practice What You Preach

💡 Why Software Organizations Eat Their Own Dog Food

Examples

🎯 Why We're Obsessed With Dogfooding at Livecycle

Research

🔎 Practicing What We Preach: Modeling the Way for Students by Developing Faculty and Staff as Leaders