Making the Case for Human-Driven Creativity

Keeping learning and mission at the center of "AI-in-Education" discourse

The Brief Case 📚→💼→📈→📊

Advances in generative artificial intelligence (most recently ChatGPT) have raised the alarm among teachers and school leaders.

“Is this the death of homework!?”

“Of the analytical essay!?”

“Of our jobs!?”

“Of Making the Case!?”

While it is still too early to say anything definitive regarding the above, we do feel that ChatGPT and other generative AI products lead to natural, even healthy, inquiry about learning and creativity. A stiff challenge or constraint can, at the very least, help us to get clear first about our beliefs and next about our options.

Facts are facts. ChatGPT acquired a massive user base out of the gate. It reached one million users faster than many tech products that have become cultural mainstays. Investors, meanwhile, have continued to inject money into the ecosystem that spawned it. As reported by Financial Times, and according to PitchBook, “Venture capital investment in generative AI has increased 425 percent since 2020 to $2.1 billion this year.” Users and funding help founders overcome what is described as the “cold start problem,” which often causes big ideas, framed as companies, to die. This current phenomenon, on the contrary, appears to have both the momentum and the funding to last. How we react shows something about what we believe; what options we generate, on top of that belief, shows how we will lead.

When a typical entrepreneur saw ChatGPT for the first time, they were likely to ask, how can I build something with that? They might have arrived at this question (and the options that it generated) because they believed that experimentation can lead to products or services that might generate profit or at least further learning.

When a typical teacher saw ChatGPT for the first time, they may have been more likely to first think about the ways that students might use it to cheat on assignments. Or, slightly more positively, they might have vocalized that such a product would cost them time; they would now need to change their prompts or assessments. Like the entrepreneurs described above, these teachers reacted to ChatGPT based on their beliefs — about the purpose of assignments, about the types of prompts we should be offering in schools, about the uses of assessments, about students themselves.

ChatGPT is certainly an interesting tool. How we and others react to it can indicate beliefs about learning and the creativity that drives the best versions of it. Are our beliefs leading to the options we would hope to see for our students, our staffs, and ourselves?

📚 The Learning Case for Human-Driven Creativity

While schools are figuring out whether to ban ChatGPT or how it will fit into their anti-plagiarism policies, it’s important to remember: nothing about good human learning should change in the face of increasingly advanced AI.

Learning at one level is about generating correct answers. When teachers believe that this level of learning is important, they will likely assign tasks that ask students to ignore easily accessible technology (calculators, Google) or to memorize facts and figures. Their assessments, meanwhile, will ask students to pick an answer from a list or to be very precise in response to a static situation. Students may not need to show their work; they may or may not get credit for showing their work if they do.

To be clear, we don’t characterize "helping students arrive at the correct answer” as deep learning or an appropriate aspirational peak for any teacher or school. Learning at a deep level is subtly and essentially different — it’s a matter of developing a significant understanding of the way(s) of reaching a correct or workable solution. If teachers believe that this deeper level of learning is important, they will prepare students to face — and relish facing — novel situations. Their assessments, meanwhile, will ask student to pull from their past experiences and knowledge to make some step forward (for themselves, for others, etc.).

In the face of rapidly improving and accessible generative AI, shallow learning and teachers who seek to inspire shallow learning might ultimately be considered easily replaceable. Deeper learning and teachers who seek to inspire deeper learning, on the other hand, will continue to be essential. In fact, the need for great human teachers (and parental figures) will likely become even more apparent because of another deep learning need to which generative AI points: discerning between probabilistic reality (i.e., AI-generated nature) and actual nature.

Many AI systems that use their initial, pre-launch training and their actual, in-the-world training continue to make data-driven guesses at what a correct/acceptable output might be. And these are not even guesses but rather IF/THEN/ELSE statements happening at a speed, density, and scale which has not necessarily been commercially experienced before.

Humans, in our way, do something similar when tapping into prior knowledge, experiences, and connections in order to provide a response, idea, or action. In terms of that task — tapping into prior knowledge, experiences, and connections — we are not nearly as effective as even a decent generative AI model; our search can never be as sequential or complete; but we do have one advantage, at least currently. In the moment before suggesting its answer, generative AI is not (yet, at least) seeking the kind of feedback for which humans are hard-wired: that is, feedback from others, from environments, from context, from body language, from culture.

Perhaps an AI tool might ask for a rating of its response as part of its workflow in order to help improve its training, but that human-in-the-moment feedback is not part of the AI’s initial response. Such a rating, its best version of “reading the room,” will only inform future interactions (which is not a bad thing but surely a limitation).

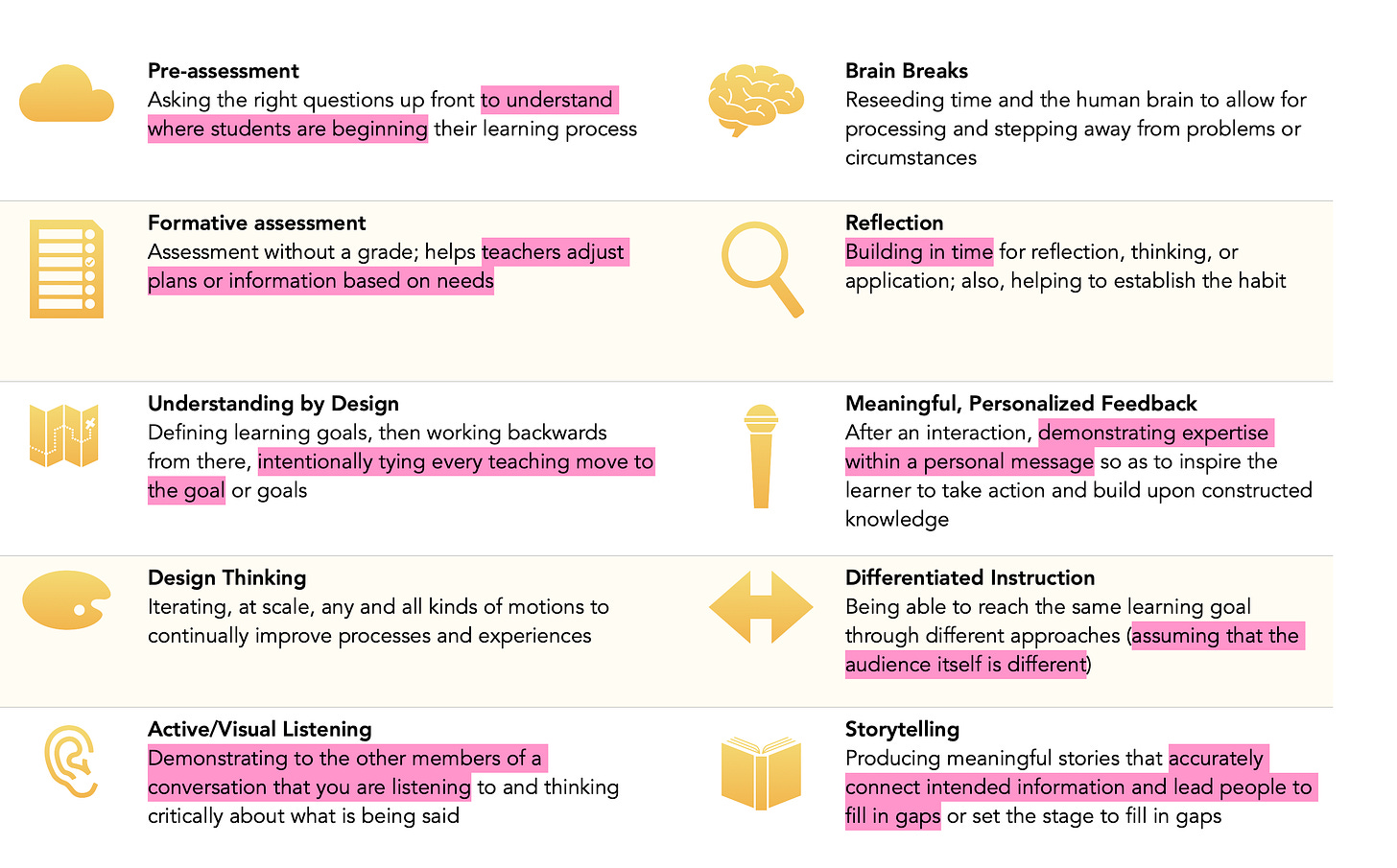

Some would argue that a great (human) teacher’s ongoing advantage, passed on to their students slowly and meticulously, exists in the small adjustments they make as a result of their relationship with and proximity to the students. The list below comes from Make Yourself Clear: How to Use a Teaching Mindset to Listen, Understand, Explain Everything, and Be Understood. It boils down the research-driven educational practices that inform the best teachers as they design, lesson by lesson and unit by unit, learning experiences for students. The highlighted sections show those places where effective learning design is tied to moves that, currently, only a human can make.

To guide a student toward durable and deep learning, we contend, the best teachers accesses some of what a generative AI can access — prior knowledge, experiences, and connections — and most of what a sensitive, thoughtful human can access — understanding where students are, demonstrating expertise with a personal message, leading people to fill in particular gaps, etcetera.

Speed, density, and scale will, no doubt, continue to advance in ways that push the limits of what human development can keep up with. That might be okay, too, as long as the advances are being used to help humans do what they do best — being creative, exhibiting emotional and interpersonal intelligence, and finding fulfillment in contributing to something larger than themselves but not at the expense of the wellness of themselves or others. That’s our belief at least, and we’ll be leaning on it to generate options for the schools and people with whom we work (and the children we are currently raising).

💼 The Business Case for Human-Driven Creativity

From a learning perspective, we recommend that you think about generative AI by framing conversations around learning rather than technology. Interestingly, this was a common mantra when the 1:1 laptop movement was happening at schools. We may have temporarily forgotten it in the face of something that seems more challenging to our teaching worldview (or at least more provocative than a MacBook Pro).

From a (non profit) business perspective, we recommend that you work to keep your mission front and center as you, or your agents, wade into what is possible and what becomes possible for your school.

Here are a few scenarios to consider:

The person who staffs your front desk, at the main entryway to your school, is about to retire. When you begin to consider possible replacement candidates, someone from the tech department brings you a proposal about automating the function. Phones can be answered and routed by a simple robot, they claim. And access to the building can be granted using a thumb print and camera system connected to the central security office. All of this would come at a fraction of the cost of hiring another person to handle the role.

Your Director of Academic Affairs brings you a proposal about the school’s curriculum guide. Families use this guide to choose courses each year. It is one of the most important school generated documents for them to actually read and understand. They would like the school to purchase a program that uses AI to read certain sections out loud, in a voice and vocal tone selected by the user. They claim this affordance would help families to process key information when they are selecting courses or getting to know the school. The program will require an annual fee, which feels slightly expensive.

You have a rogue English teacher who, trying to prove a point about the inevitability of AI, allows students to use ChatGPT in their writing assignments to generate first drafts and then edit those drafts into a final draft.

Regarding the robot front desk attendant: if your school aims to cultivate a healthy climate, one focused on SEL and community building, then such work often begins with a student’s first daily touchpoint. A thumbprint machine cannot greet them by name; and a grainy image beamed to a central office will likely not reveal if a student’s demeanor or emotional state (or, as the kids might say, “vibe”) feels different today than it usually does. And as for the phone. . . a live voice might increasingly feel like a luxury, but we likely want to continue to do all that we can to make our schools feel less like corporations (routing transactions via call centers) and more like, say, a farmer’s market where even the most transactional of encounters seems to feed a higher purpose and holds out the possibility for human connection and relationship.

Regarding the robot that reads the curriculum guide out loud: If your school’s mission aims to make opportunity accessible, and to constantly examine and boost equitable practice, then adding a reader, even a non human one, to an important community document might be on point. People, after all, have different learning styles and different ways of processing information. A school that centers only one — in this case, processing through reading a static PDF — could have some room to grow.

Regarding the rogue English teacher pushing ChatGPT: What commitments does your school make to develop analytical thinking? How does that belief lead to options for scaffolding among and between grade levels? What implications would it have — for your mission and purpose — if you introduced Chat GPT into the scaffolding too early? Would you create greater analytical options for your students down the road or somehow diminish their ability to operate in an analytical way (or environment) down the road? (Also, check the terms of service and square them with your AUP. The conversation might not be that deep. H/T to E.B.)

As AI becomes better, it will no doubt make things possible (we already rely on it much more than we likely know, as it is baked into products like GPS). Assuming you are uncovering new ideas all the time and they are flowing into your decision making systems, we suggest three questions for business operators considering enhancements or disruptions, in the Clayton Christensen sense, suggested by AI:

In situations where AI offers your organization an affordance, something you can do to add an efficiency: Should you? (This is largely an ethical question, one we would not only want to utilize in our decision making but also embody as institutions that aspire to create the next generation of leaders.)

In situations where AI offers your organization an affordance, something you can do to advance your school’s mission: Why shouldn’t you? (If you value your mission, and your leadership actions are tied to it — and can plainly and confidently say, we do this, not that — then if you’re being honest and rigorous, questions about AI aren’t necessarily questions about technology. They are questions about mission.)

And what will you do with the time you save if you decide to automate and discover substantial efficiencies? (This question often causes negative reactions because it exposes the fact that we haven’t taken the time to really think through our beliefs, our actions, our behaviors, or the deep why of our work, our institutions, our structures, and our communities. If AI promotes more of that kind of inner work and subsequent deep learning for the adults in your community, and then actually leads to positive actions, then its costs seem worth exploring.)

📈 Return on Investment for Human-Driven Creativity

Measuring the ROI of the results of a human-driven creative project/change can be as simple as comparing the impact of the project/change to the impact of the last project or change in that same area that took perhaps a less creative approach. This would be comparing a new cycle to a previous cycle.

For example, each year a goal of an enrollment management office might be to have a higher number of qualified students apply for admission. The control might be the change in qualified applications year-over-year (YoY) from some previous period (e.g., from 2020 to 2021).

Now imagine some creative approach was designed. Your measurement of the ROI in that creativity-enhanced approach can be tagged as a contributor to the change in dimension you wanted to see (e.g., from 2022 to 2023).

At a much smaller scale, you can run some A-B testing during a pilot phase before introducing a larger change. It’s the same basic principle.

📊 Return on Learning for Human-Driven Creativity

Considering the enrollment management experiment described above, you could measure the Return on Learning by ask whoever is on the contributing team to the creative approach to reflect on their own creativity as a result of the engagement.

Whether it was by partnering with a diverse group of folks on the team, or using a newly introduced generative AI to foster thinking, what matters in this assessment is the extent to which the engaged participants feel more creative.

If a generative AI product or service was used to help a team be or at least feel more creative, perhaps by jumpstarting a brainstorming session, providing a basis for comparison, or offering quick feedback, then it’s worth keeping it in your team’s toolbox. If it’s being used as a substitute for creativity or a bypass for the necessary messy and difficult teamwork and conversations that produce truly special results for a particular institution, at a particular time, and in a particular place, then it should be avoided. Only a human leader knows the difference.

More on this Topic

Opinions

💡 AI and Design: why AI is your creative partner

Examples

🎯 Brxnd: an organization at the intersection of brands and AI

🎯 Getting to know—and manage—your biggest AI risks

Research

🔎 Creativity and Artificial Intelligence—A Student Perspective

🔎 Developing Creativity: Artificial Barriers in Artificial Intelligence