Making the Case for Starting

Starting to Finish Making the Case

The Brief Case 📚→💼→📈→📊

“Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets“. —W. Edwards Deming

“In a way, we moderns resemble a painter who is forever concerned about improving their tools—the colors and brushes, the air condition and lighting, the canvas and easel, and so on—but never really starts to paint.”—Hartmut Rosa

Something bad happens. Something good fails to happen. In these moments, we often point to people when we should be pointing out systems.

An example:

A Campus Head is becoming increasingly concerned about the English Department at her school. Not because of the teaching or the reviews from families. Those trend lines are strong. But she’s starting to field more and more questions about the books being taught in the curriculum. In almost a decade, they haven’t really changed.

In a meeting with the English Department Chair, she begins: “What’s going on with your teachers? Their book selections are feeling stale, no?” What follows is a lot of speculation, then wondering, then outright judgment. “Well,” says the Chair finally, “you know Charles and Tim. They’ve always been stubborn. And they just don’t want to grow with the times.” The Campus Head, at this point, knows full well that she doesn’t have enough data to follow up on a claim that may or may not be true and, if pursued with Charles and Tim, could lead to a long discussion that boils down to a wrestling match over semantics.

The Campus Head changes directions with the Department Chair. “Let’s look at this from a different perspective. Can you describe the book ordering process? How do books actually get into the hands of students?” The conversation that follows will not be about the teachers in the department. Instead, it will be about the way a particular system generates the precise outcomes it is designed to produce. The Campus Head might find out that the bookstore manager “always asks for the book orders a week in advance of when she needs to place them with the school’s book distributor.”

By zooming out, therefore, she learns: each year, a systems-level decision puts the English Department in a position where they simply do not have time to make thoughtful decisions about the books they teach. Instead, they cut and paste last year’s orders and move on with the mountain of tasks that they confront each day. Some might call this “satisficing," i.e., good enough given the circumstances.

How might the Campus Head and Chair change the system to change this outcome? Put another way, using one of our favorite questions, what's the smallest possible high leverage move?

The Chair controls the agenda of her own meetings. She basically has the same 10 meetings, at roughly the same cadence, every year. Because of their predictability, these meetings can be seen as a conveyor belt of sorts, where the department has clear, set-aside moments to consider and work on the products they produce. Following this logic, the Chair can re-consider when she wants her department to consider and work on their book orders. She can declare -- in a fun way for any English teacher -- that December is going to become a book buying and sampling time for the English Department. If she has some money in her budget, she can purchase one or two books per faculty member and ask them to read the books over the holidays. Then, in January, at the first department meeting of the new year, she can ask each faculty member to offer a short review of their book with the intention of altering at least 10% of the department's book orders come May. Following this plan, the runway to book ordering will be longer. And the book ordering system will be designed to produce a different outcome.When you see the difference between people problems and system problems, you realize that you have leverage with the latter but maybe not so much with the former. It is one thing to say, “Hey teacher/administrator/colleague/Trustee: change; become less stubborn; become more stubborn; grow with the times; etc.” Has that approach ever worked? It is another thing altogether to understand where a person or team fits into a larger system…and then to change the system so that the person or team is positively swept up in it, allowing their better (or at least different) angels to prevail.

Every systems thinker knows the difference between fretting over the results of a system and adjusting the system upstream of those results. It is a matter of where you want to spend your time and, frankly, how much you care about the results. Which brings us to our true beginning: leadership is often as easy, and as hard, as starting.

📚 The Learning Case for Starting

The COVID pandemic and how independent schools experienced and led through it continues to provide helpful lessons and reminders. That period of time was scary for many people because they were forced to “start.” Some may even have developed an associated institutional trauma with “starting” as a result, incorrectly coupling change with major/dangerous/tragic events. Regardless, it’s often easier to begin something new in a crisis.

But what about the ordinary days? How do we learn to pull up on a regular Tuesday in October and abruptly say: “We’ve recycled this bad outcome long enough. We’re going to get into this.”? Building or arranging a system is skills-based work. Knowing when to intervene in a system is judgement-based. Deciding to actually intervene is courage-based. Whether such courage is dramatic or ordinary, it is a key to ensuring that your school year doesn’t play out like a version of the movie Groundhog Day, where the same problems keep happening.

Stop for a moment. Take out a piece of scrap paper or open a file on your laptop. Think back to September of the current year. Make a list of those problems that popped up or came across your desk or caused a traffic jam in your inbox. Circle or highlight the problems on the list that were not new. That is, identify the problems that happen year after year (and likely at about the same time each year). You likely see problems like the ones that follow:

We forgot, again, to fix the confusing question on the Spanish placement.

Our website is broken in exactly the same way that it was this time last year.

The map of our campus again caused parking issues on Back-to-School night.

Our evaluation system is still a mere shadow of what it needs to be. And now teacher x or administrator y is causing the problems that they always cause, seemingly beyond reproach.

We still don’t really know the new neighbors, and they are mad at us — again — because the inter-town rivalry football game was — again — too loud.

We could go on…

Something bad happens. Something good fails to happen. In these moments, we often point to people when we should be pointing out systems…which leads, contradictorily, back to people. Unlike a water leakage detector in your home or a flag in your inbox that says “this might be spam,” most of the spanners in human-based organizations need to be thrown by the very humans who inhabit them. Humans decide to ask systems questions. Humans decide when to break inertia. Humans embrace a bias to action. And, in so doing, humans build habits and muscles around starting. This, in turn, makes them effective leaders.

We want students to be motivated self-starters. We want new employees at school to learn to be motivated self-starters. In fact, this is the very trait that we call out when responding to secondary school and college recommendation forms for students, or reference calls for faculty looking to move on from our schools. We talk and talk and talk (and talk) about building and being “lifelong” learners. But if such learning does not, at some point, spring into action — attempting to reshape the world — then maybe it is not worth as much as we charge for it.

As we have stated many times in the past, leaders lead the learning of others and learn by leading. And as we will say slightly differently in the future: leaders lead the application of the learning of others and learn, themselves, by starting.

💼 The Business Case for Starting

Squint, and you can see that schools naturally have a product cycle built into them. The academic schedule naturally leads to curriculum review and publication (so that students can sign-up for next year’s classes). It leads to hiring. It informs future budgeting. All these highly variable elements of running a school are actually very predictable.

Other industries have to determine — or more often have determined for them — a product cycle that may not be the same year-over-year. In some ways, therefore, schools have an advantage (when compared to other industries) of knowing they have both:

a defined product cycle; and

a low likelihood of disruption to or fluctuation of that cycle.

However, a school’s product cycle can also lull it to sleep because so much of it is automatic; over time, folks almost forget that they are producing a product, or they never really embraced that ethos in the first place. They are just doing school. They are just getting set up for next year. They are just running it back, hustling until the next long break.

There is nothing wrong with hard, focused work. Schools would collapse without it. But go back in your school’s history, wherever you keep the records of things your predecessors were struggling with, and you will likely find that today, likely right at this moment, you are dealing with some version of the same problem that appeared in 1973…and again in 1986…and again in 1998. Enrollment challenges. Facilities challenges. Schedule challenges. Curricular challenges. Discipline challenges. Supervisory challenges.

Fortunately if you work in a school, starting on any of these challenges can easily slot into the groove of a very natural cycle. And the cycle probably has more supporting structures than you realize. Some believe that making changes creates instability. Let us think of it in another way: Change exposes existing instability that, once stretched beyond the point of sustainability, forces the start that was being avoided anyway. You can see this easily when a program is sustained too much by the efforts of a single person. When that person leaves, the program falters, sputters, and then eventually disappears. Change did not create that instability; it exposed it. A good leader sees such failure (a particular flavor, to be sure) as a moment to start a rebuilding process that is far more anti-fragile.

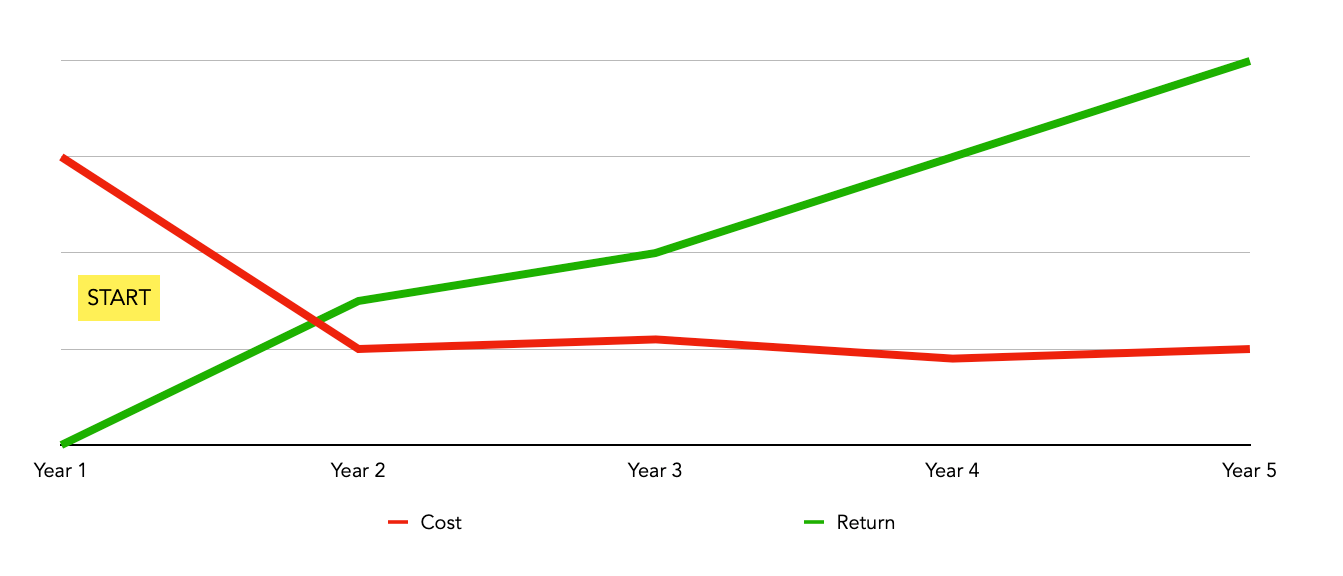

📈 Return on Investment for Starting

Starting the thing you have been meaning to can open the doors to the things that are dependent on it (i.e., we can only do Y if we first do X). So, do X (or a version of it). The return on investment is unleashing all the contingent possibilities, knocking down all the adjacent dominoes, seeing the thing you could not see because there was something else in the way…

You cannot measure the near term actual returns and model out long term potential returns if you never get started.

📊 Return on Learning for Starting

Also, if you do not start, you do not learn. Put another way, once you start, and start learning, you can refine and expand the lessons that starting produces. Take a look at something you started. How much of the learning/feedback is related solely to the thing itself? And how much of the learning/feedback applies to other aspects of your school?

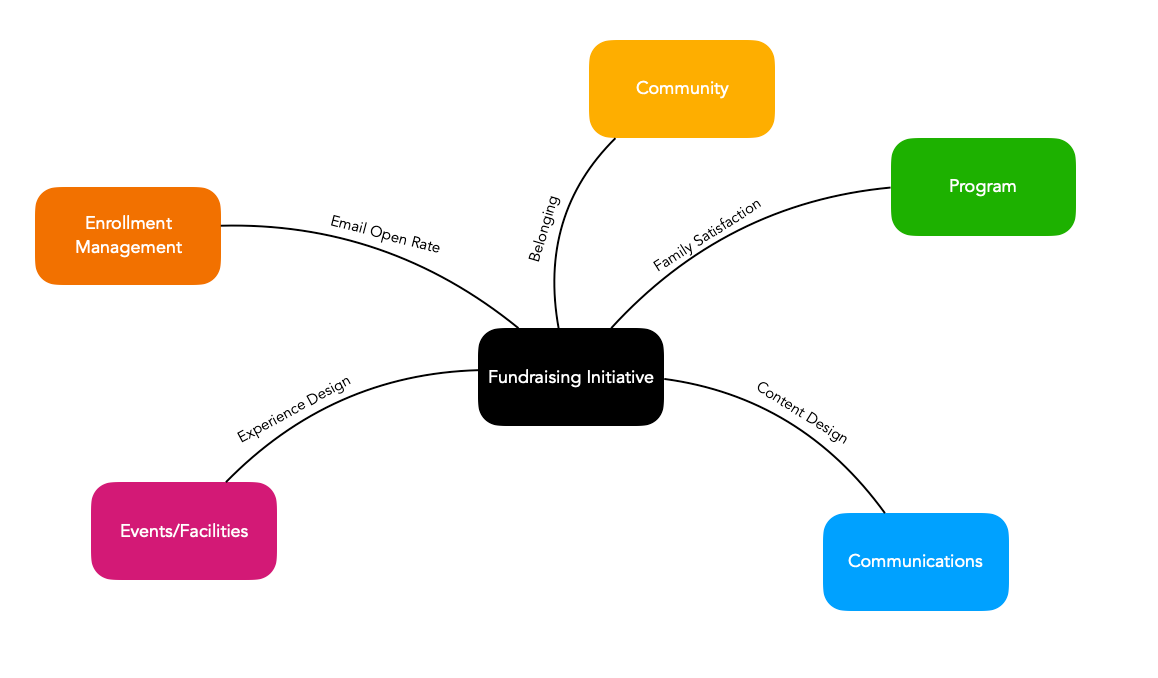

Say you recently launched a fundraising campaign. Starting such a campaign will teach you about the appetite for fundraising in your community. And the return on a certain strategy. And which events “break even” and which events lead to net gains. But you will also learn about other aspects of your operation — if you are open to such lateral learning. In this Development example, you will likely learn about your institutional email/communication habits. Such learning can then be applied to your next crisis, your next celebration, or your next community-wide survey.

Next time you have started a new thing you have been meaning to get going, map out the potential areas that the work effort will also help.

You learn once you start — and, one caveat, starting does not mean being hasty or sloppy. It means being thoughtful about your minimal viable product, launching it, learning from it, iterating it, and improving it. Be a school that learns. Be a school that also acts on its learning. The students that we expect to change the world have always been watching.