Making the Case for Finishing

Finishing the start of Making the Case

The Brief Case 📚→💼→📈→📊

Some tasks are never finished, and never should be: building and participating in school community each year, building and refining systems that honor the dignity of all people, building and maintaining one’s own health. But many other tasks in school are never finished but should be, even if the finishing is only temporary. Your evaluation system for employees. Your goals for the year. Your time in your inbox each day. Schools and their leaders often mix up work that is ongoing with work that, for one reason or another, just doesn’t finish.

As ever, when trying to make sense of our increasingly atomized days, naming helps. We would bet that most of a leader’s responsibilities can be sorted into two columns. Some work is likely “evergreen.” And the rest should be “defined projects or tasks” — that is, work that has a beginning and an end.

If you actually go through this sorting exercise, you may find that you are not sure where to place certain items. Such indecision simply tells you that you have not spent enough time thinking about what it would look like to bring those items to completion. Adding them to the “defined projects or tasks” column will force you to quickly revise them from something generic like “Tom meeting” to something with a defined outcome and end like “Tom meeting to decide about program direction.”

Once you have your lists sorted out, you will gain important clarity on which projects or tasks need ongoing maintenance and which projects would benefit from something entirely different: a clear end.

Note to readers: This will be the last edition of Making the Case, version 1.0.

What began as a way to help point to, unpack, and bridge the sometimes murky gap between senior leaders and Trustees in non-profit institutions (especially schools) became a trusted framework to lead and manage change.

When a work product takes on a life of its own, it’s generally a good time to move on to something new. We will share updates soon and use this subscriber space as a spot for an experiment or two, but first we have to finish what we started… 📚 The Learning Case for Finishing

We learn by doing. But we deepen and refine and make permanent that learning by reflecting. Such work requires a ledge. A carve out. A place and time from which to be able to contemplate a horizon.

We have previously written about the judgment and courage needed to start. The same ingredients are required for getting out onto that ledge, inhabiting that carve out, and contemplating that horizon. That is, all endings require both the judgment and the courage to finish what one starts.

It is okay to acknowledge that endings can be mere constructs. Is anything ever really finished? No. But almost anything can be broken into phases, which by definition, can be finished. Also: You can finish an iterative cycle. You can retire something that is no longer serving your institution or you. Finishing, of the sort we are recommending, is therefore an act of imagination just as much as starting often is. Semantics? Sure. But also practice—and dreaming.

Think of the progress bars used in the setup of new software or apps. Yes, the designers of these projects may be leveraging, or even exploiting, our desires to see such bars go away, fully completed. But so, too, are the great literary authors who relied on a few basic plots with predictable but satisfying dénouements. Both setups and their satisfactions say something about the human condition. Having no end in sight feels daunting. Finishing a step in order to move on to the next step, task, or project fuels reflection, momentum, clarity, progress, and crispness—all good things.

Think of a disciplined runner logging miles. She likely wakes at the same time, laces up her shoes in the same way, powers up with the same general fuel, and steps out the door—controlling what she can control and gritting out the rest. Over time, her physiology changes to meet the task and she builds her reserve of mental toughness. This daily grind is good, but its impact can likely be enhanced by adding the occasional race to the schedule. Competing allows daily runners to push and then measure their paces. Such new knowledge often animates and adds purpose to daily training.

Think of Kanban boards used to bring order to the sometimes chaos of startups. Such externalizing instruments help individuals and teams to visualize their progress and make sense of their work by finishing, then logging, things that were started.

Think of a deft teacher’s move from formative assessments (that build skills, knowledge, and confidence) to summative assessment (that tests those things) and then back to the formative with increased sensitivity to the particular needs of a particular set of students.

The chance to observe, then make sense of, then adjust the baseline of one’s performance is key here. If you are forever in motion, forever in the game, forever wrapped around the axle, you cannot make sense, you cannot exercise judgment, you cannot benefit from a proper accounting, and you cannot make a responsive adjustment. Which could make all the difference in where you ultimately end up.

💼 The Business Case for Finishing

Here are some reasons things fail to finish in schools:

A process begins enthusiastically but no one asks, “how will we check in on our progress?” Or, more potently, “How will we know that we should keep going down this path?”

Clear decision-making authority is never assigned or articulated.

Things simmering along on a proverbial back burner are never brought to a boil. (It’s amazing what a short burst of focused and intense work can do for important projects that are hiding out beyond the daily urgencies and emergencies.)

Personal systems that fail are never interrogated or coached; in such cases, the day-to-day is all there is and projects or tasks will remain, uncompleted, in the background.

School systems are leaky or unclear, seeping into every second of an employee’s day. Such environments, by definition, reduce the possibility of reflection and adjustment.

There is an endless collaborative habit at work. While collaboration is widely and justly celebrated as a positive, every strength has a shadow side. Beyond tennis without a net, endless collaboration can become tennis without a scoring system to tell the players when the game is over.

All of the above can lead to individual fatigue and institutional fatigue and cause people to think, if not ask: Why are we around this table? Why are we in this meeting? Why are we having the same problem that we had last year?

The next time you begin a project, acknowledge that you are in startup mode and that one of the most important goals of startup mode is to graduate from it—to finish it and then enter a new phase, i.e., maintenance mode. The beauty of making this transition is, in part, that a project in maintenance mode is repeatable; and as such, it becomes part of a school’s ongoing value proposition (whether for employees or students or parents or whomever). It is plain-old-predictable, a promise you can deliver on, an expectation, a standard.

And there is more. If you finish, you can measure impact. If you finish (and uncover impact) you can market that impact. If you finish (and uncover impact and market it well) you can reinvest and double down. Finishing—often—charges up your school at the cellular level.

📈 Return on Investment for Finishing

A new course. A new speaker series. A new program for the entire ninth grade. A new curriculum. Being in startup mode can be a lot of fun. It’s a time when new ideas are welcome, creativity flourishes, and the reality of what might be called product-market fit is not bearing down on anyone. As such, startup mode can also be expensive and steeply so, especially if you stay in the experimental mode for too long.

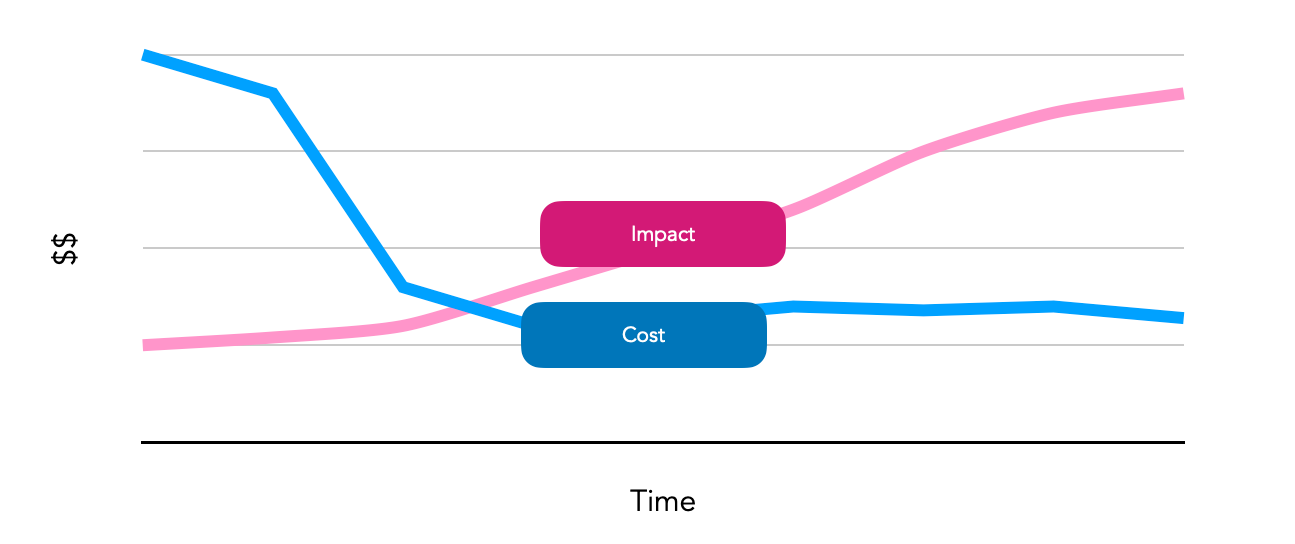

The good news is that if you can finish startup mode, if you can graduate the project, you can move it into maintenance mode, making budgets predictable and systems transparent. Predictable budgets help business and development offices to settle down and to settle in for the long haul. And transparent systems allow for continuous enrollment and onboarding. As cost levels out and impact continues to rise, a school can confidently assert that it is on the path to success.

📊 Return on Learning for Finishing

Look at the strategic goals for any schools in the midst of a strategic plan cycle. You will likely see something around “program excellence” or “academic innovation.”

A more strongly-framed goal might be “to increase perception of academic excellence from [insert constituency]” or “to aggregate student performance results via a norm-referenced diagnostic.” Then, and depending on the ongoing results, school leaders can organize their work around their real challenges: are they having an execution issue (what’s happening in the classrooms)? Or are they having a communication issue (how the program outcomes are shared with an identified constituency)? And if they are experiencing (likely) some combination of both, then school leaders have two areas of work to start and finish.

Look, too, at the goals that school heads set for themselves or the institution. Often, such goals are merely articulated foci of job responsibilities or ongoing parts of an organization’s work (e.g., “to support the onboarding of a new administrative team member” or “to cultivate donor engagement”). Instead, the goals should be measurable results that can be tied to the responsibility (e.g., performance review about the new administrative team member that includes their self reflection/report on job satisfaction or a target number of donors or volume of giving from current donors).

We enforce a similar process with students all the time—there is an assignment and expected criteria for finishing (and finishing well). As we have posited many times before, the best schools are consistent about their approach to learning whether that learning happens in a Board meeting or in a kindergarten classroom.

More on this Topic

You can find the Collected Making the Case, Version 1 here. Pointing to it with finality will allow us to do something new. Hopefully you can, too. Thank you for your attention. Thank you for your encouragement. We hope to continue to earn both.

Okay, that is all. We have finished.